For those of us who believe in the market, impact investing — the idea that we can address the world’s social, environmental and health problems through the market without sacrificing financial returns — is an attractive one. And it’s a concept that has gained significant sway in recent years.

But as the challenges facing our economies and societies mount — and the cost of addressing these keeps on rising too (the UN Environment Programme estimates that the global cost of adapting to climate impacts is likely to grow by $280bn-$500bn per year by 2050 for instance) — cracks are starting to show in this narrative.

The simple truth is that sometimes you can’t have your cake and eat it. Sometimes there is a trade-off between profitability and impact, and much of what we must do to address the world’s environmental and social challenges is going to be unprofitable in the conventional sense. As Alan Schwartz and Reuben Finighan write in Harvard Business Review, “impact investing won’t save capitalism”.

This is not to say impact investing in its current form is failing. On the contrary, this innovative investment philosophy has heralded the beginnings of a market approach to social, environmental and health challenges that has irrevocably changed the way we think about these things, and that is significant. Not too long ago, for instance, taxpayers, corporates and foreign aid almost exclusively picked up the tab for putting in place projects and initiatives to address such challenges.

Back then we relied either solely on the benevolence of foreign nations and governments in the form of aid, or on the kindness of corporates through initiatives they set up under the umbrella of social corporate responsibility to address these issues. But both these approaches have run into problems of their own.

Foreign aid, a growing consensus would claim, has fallen short in its goal to inspire sustainable economic growth or make significant inroads into poverty reduction or any of the other UN sustainable development goals (SDGs). Too often, critics say, any potential good was eroded by bad governance, weak rule of law, corruption, a dearth of strong democratic institutions and little accountability. Corporate social responsibility has in turn been sidelined as unsustainable at best, and at worst a distraction and “window-dressing”.

Impact investing, by contrast, succeeds in bringing the resources of the market to bear on the world’s challenges. As an investment strategy that straddles multiple asset classes, impact investing can attract and direct investments that generate positive and measurable social or environmental impact alongside financial returns.

Optimism is warranted

Significantly, impact investing heralds an appetite — within the market itself — for a different take on investing as a whole. The world has come to understand that we need to rethink “poverty” and that traditional approaches to poverty alleviation often unintentionally perpetuate cycles of dependency and further marginalise those in need.

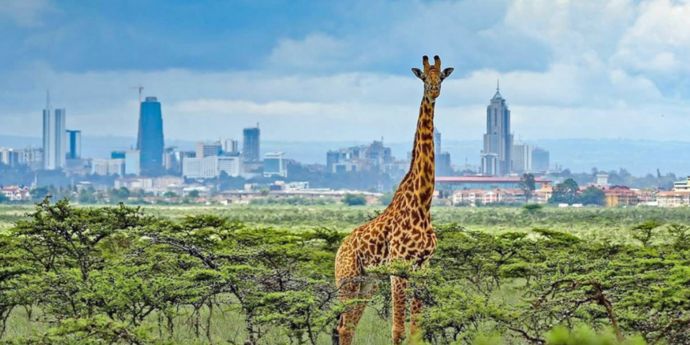

There is a clear appetite among investors themselves for this kind of investing. In a 2022 market sizing report, the Global Impact Investing Network estimated that more than 3,349 organisations manage about $1.164-trillion in impact investing assets under management. And in Africa the launch of the Africa Impact Investing Group at the inaugural Africa Impact Summit held in Cape Town in July points to impact investing building up a head of steam on the continent.

That said, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that impact investing has shortcomings of its own to address. If it’s easy enough to measure the financial return on an investment — it’s right there in hard currency — then social and environmental returns, impact investing’s greatest advertised strengths, are also its “greatest weakness”, as at least one scholarly article argues. An array of impact measurement tools — such as the UN SDG Impact Standards — are being identified, developed and applied, but progress in this regard remains patchy and inconsistent.

Evolution continues

While I am someone who teaches and preaches about the virtues of impact investing, I am also a partner in a private equity firm so I straddle these two ideological worlds. It is inevitable that within that environment we often have to stack those hard-to-measure virtues of impact investing up against other investment considerations.

In such situations it can be helpful to think of impact investing, as Kresge Foundation trustee Jim Bildner does, not as the only game in town but as part of a larger investment climate where different kinds of capital, including philanthropic capital, government and development funding, and business capital, can work together in building more resilient and equitable communities and economies. Perhaps it is acceptable for impact capital not to always have to compete for the most competitive return but to play its part in helping set up the conditions on the ground to be investable for conventional market capital.

Few investors say they are willing to accept the trade-off between impact and returns, but we can shift this binary thinking if we use the disruptive ethos of impact investing to start to rewrite the rules that govern how our economies work. For starters, if capital providers can work together to achieve targeted impact, based on the understanding that we all want — and need — the world to be a safer and less divided place, then perhaps all investing can become impact investing.

Steenkamp is co-convener of the Impact Investing in Africa executive development course at the Bertha Centre for Social Innovation & Entrepreneurship, University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business, as well as a partner at Seedwell Capital Fund.

This article first appeared in Business Day